In 1949 Sara Lee Creech, a businesswoman and social activist of Belle Glade, Florida, observed two African American girls playing with light-complexioned dolls. Creech thought it was wrong that the girls had no dolls to play with that looked like them, and she became determined to provide an “anthropologically correct” doll for black children. When she began her quest, Creech may have not known how truly important her doll idea would turn out be.

In the 1930s and 1940s, child psychologists Kenneth and Mamie Clark studied young children’s preferences for light and dark complexioned dolls. Black children often choose to play with the lighter dolls, suggesting that by the time they had reached nursery school, these youngsters had already accepted society’s prejudices about their own race. (The Clarks’ findings applied especially to black children attending segregated schools in the South, and these studies played an important role in the NAACP’s battle in the 1950s to end segregation in public schools.) Creech came to believe that a well-made doll that accurately reflected the beauty of African American children might help them overcome the self-rejection resulting from what one historian called a “corrosive awareness of color.” As Gordon Patterson observed in article about the Sara Lee doll for The Florida Historical Quarterly, “This was about using popular culture as a means of social and political reform.”

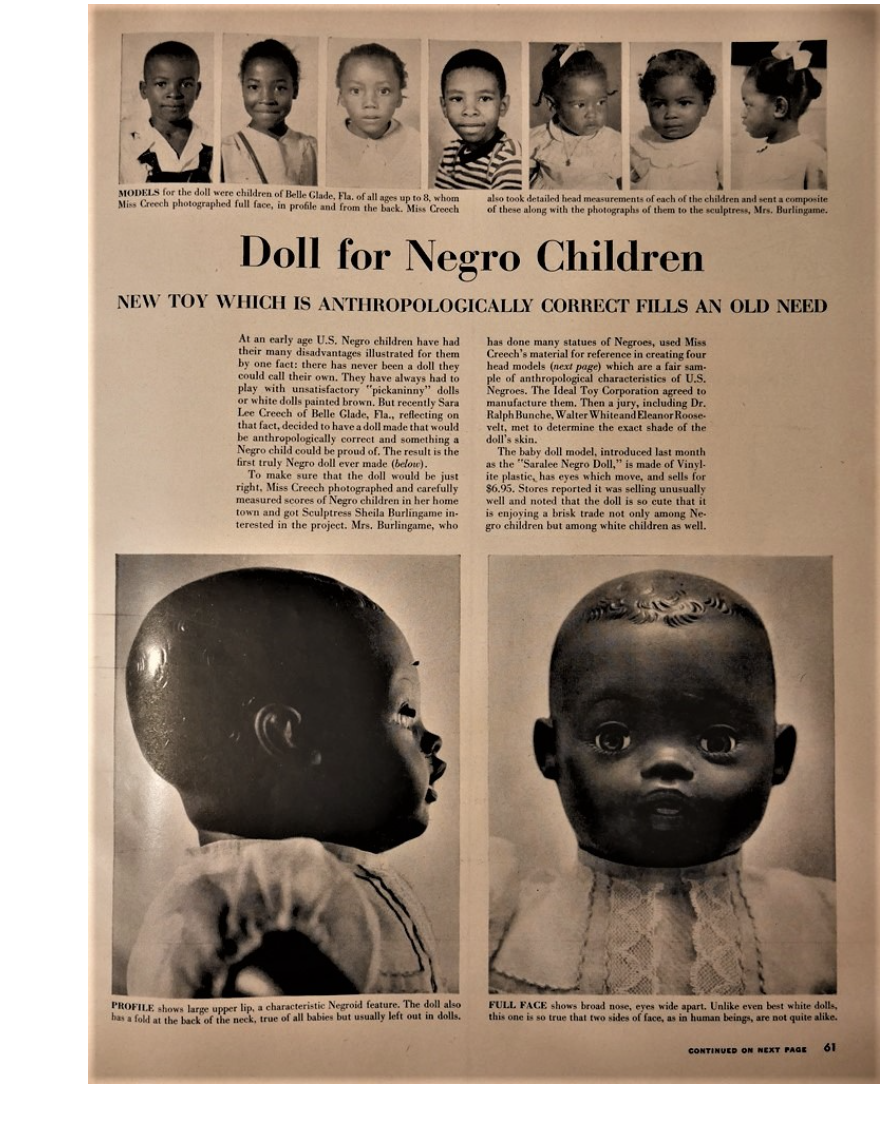

Sara Lee Creech began her crusade by approaching noted sculptor Sheila Burlingame to mold the doll head. Creech showed prototypes to African American novelist Zora Neale Hurston and a New York friend with ties to former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. Mrs. Roosevelt took an interest in the project and wrote in a letter of support, “I like them particularly because they can be made and sold on an equal basis with white dolls. There is nothing to be ashamed of. They are attractive and reproduced well with careful study of the anthropological background of the race. I think they are a lesson in equality for little children, and we will find that many a child will cherish a charming black doll as easily as it [sic] will a charming white doll.”

With the help of black leaders including Ralph Bunche, Mary McLeod Bethune, and the presidents of Howard University and Morehouse College, Creech convinced the Ideal Toy Company to manufacture the dolls. She asked for guidance from leaders of the white community too. Mrs. Roosevelt helped out a second time, hosting a tea in New York City for African American leaders and Ideal executives when the firm delayed production on the doll in 1951. News of the First Lady’s reception and doll’s availability appeared in Time, Newsweek, Life, Ebony, and Independent Woman, in addition to city and regional newspapers.

The Sara Lee doll never sold in the quantities that Creech, her supporters, or Ideal had hoped, in part because the vinyl used to make the doll hardened, lost its initial color, and seeped its dyes onto the doll’s clothing. Ideal canceled plans to make other African American dolls with a range of lighter and darker complexions reflecting a similar range in the black population that might have broadened the dolls’ appeal. The toy world waited until 1968 before releasing another mass-market black doll, Barbie’s friend Christie. Meanwhile, Sara Lee Creech continued working for interracial harmony, establishing daycare centers in the 1950s and 1960s for the children of migrant workers and testifying before the White House Conference on Day Care in 1965. Her doll may not have become a commercial success, but as Gordon Patterson put it, “The creation of the Sara Lee doll said black children are to be taken seriously. It said that toys do matter.”

By Patricia Hogan, Curator

The Strong National Museum of Play

Published on April 23, 2013

Comments